‘Mapping the Miasma’- Ireland’s 19th century Pandemic: an analysis of the 1832 Cholera epidemic.

The great Cholera Epidemic of 1832, was the most virulent pestilence to reach these shores since the Black Death. Now almost forgotten, it killed at least 50,000people on this island. Eclipsed by the tragedy of the Famine, the impact and legacy of the cholera on Irish towns and society remains under-studied.[1] I am currently engaged in a comprehensive geographical study of the epidemic in provincial Irish towns. It aims to investigate and map the narrative, geography and comparative magnitude of the event, within the context of the complex political and social events of the period. The epidemic has never been subject to mapping or statistical analysis, despite the significant amount of contemporary data available.

Extensive numerical data as recorded in the newspapers of the period allows a statistical approach to the study, as do the daily reports of the Central Cholera Board, and the specific abstract in the 1841 census. This type of inter-disciplinary investigation forms part of the emerging fields of medical history, life-sciences and public health. The study will, for the first time, chronicle and map the extent of the 1832 epidemic, allowing for a nuanced look at how disease and fever had a significantly different impact and character in urban and rural areas. Comparative case studies of Irish provincial towns will enable an examination of the experience of the epidemic at this important tier of the urban structure in pre-Famine Ireland. Data collected will allow evaluation of the Irish experience against the experience of British and European urban areas, and encourage a re-evaluation of the nature of the Irish epidemic.

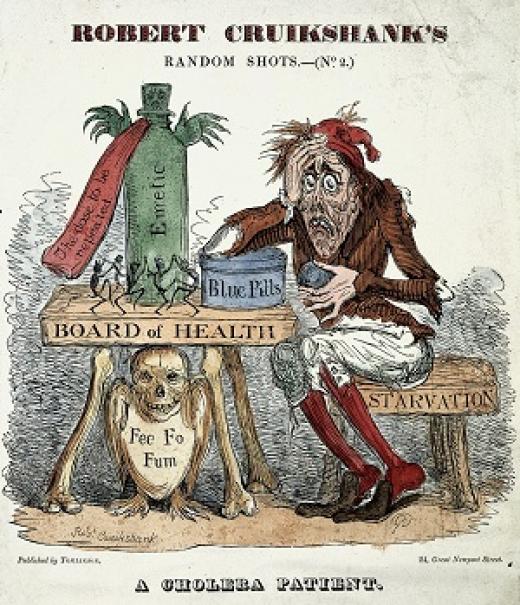

Historically, the term ‘cholera’ referred to a severe type of gastroenteritis, characterised by vomiting and diarrhoea. But by 1820, ‘cholera’ came to mean the AsiaticorSpasmodic Cholera, an epidemic form of the disease, which had been spreading westwards from India since 1817. It is an acute, waterborne, diarrhoeal disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio Cholerae. Typical symptoms include stomach cramps, looseness of the bowels, vomiting, severe pain in the limbs, and acute dehydration, which if left untreated, resulted in death, sometimes within hours of the first symptoms. It was an indiscriminate disease, not just confined to the poor.

Cholera arrived in Ireland via Belfast, on the 18 March 1832. It spread to almost every corner of the country during 1832-33, claiming at least 50,700 lives before it finally abated in the late Spring of 1833.It struck hard, but erratically, attacking some towns, while leaving others in close proximity unaffected.

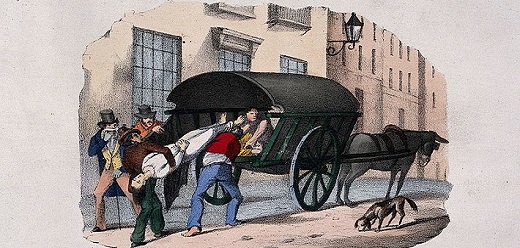

Ireland provided a fertile ground for the spread of fever. The physical condition of the people, both rural and urban was generally poor, following the severe typhus epidemic of 1817-18, and the famine of 1821-22. Regular local outbreaks of famine and fever, left an entire class of people ‘weak for want of sustenance and easy prey to disease’. Successive periods of wet summers in Ireland between 1821-30 resulted in food and fuel shortages, giving rise to an atmosphere rife for spread of infection. Thousands were reduced to begging and vagrancy, and these mendicants helped to spread disease from town to town. Rambling-house visits and attendances at wakes, made the spread of the cholera even quicker.

The economic and political state of the country in 1830 was in great flux. Full free trade between Ireland and Britain commenced in 1824, leaving Ireland’s small-scale and domestic industries highly vulnerable, resulting in a greater level of poverty. Politically, the period was dominated by Daniel O’Connell’s campaigns for Catholic Emancipation and Repeal, the sectarian Tithe Wars, and the agrarian outrages of the Ribbonmen, all compounded by the economic crippling of the poor labourer by relentless inflation.

Why map an historic epidemic? Studying past epidemics helps provide a sampling device for social analysis. Wider issues to be addressed by this study include determining the effects of the medical and governmental response to this crisis. It is difficult to be totally accurate about the true number of deaths in Ireland. Most researchers conclude that local statistics, as published in the newspapers, present the most accurate mortality figures we have.[1] Figures returned by the local Boards of Health are felt to be on the low side, recording only those who died in the cholera hospitals, or were clearly identified by the medical officers as having suffered from the disease. The manuscript returns complied by the local Boards of Health show that for 1832 the number of cases were 51,153, of whom 18,955 died; these are considered to be accurate, in so far as they enumerate reported cases. It is the omissions from the records, rather than false reporting that causes the discrepancies. Deaths in rural areas went generally unreported, as did those away from Fever Hospitals. The approximate total of 46,000 to 50,000 dead stated by most authorities must be considered a conservative estimate, and the total number of deaths was revised upwards to 55,500, following investigation of the epidemic for the 1841 census.

The incidence of cholera in Ireland was very high, much more so than in other parts of the United Kingdom. Ireland comprised 32 percent of the UK population, but suffered 45 percent of UK cholera deaths. Irish mortality rates were significantly higher; this high death rate can be regarded as an index of serious poverty in the country.

It is unlikely that this study will be able to produce a detailed demographical breakdown due to the lack of raw data. But trends may be inferred by correlation of the data with the historical narrative. Mapping can present the discrete elements of an epidemic in terms of numbers of cases, deaths, recovered, geographic spread, revealing patterns that are not obvious from printed sources or narratives.

Identification of the primary sources and extraction of numerical data is the first hurdle. These will have to be extracted manually from newspapers and archival sources. While many contemporary newspapers have been digitized, much of the primary source material for this project is contained in Irish and British archives, and will require significant investment in labour and time. Data also needs to be evaluated and assessed, and supported with narrative research. The recently catalogued records of the Chief Secretary of Ireland’s Office in the National Archives, constitute one of the most valuable collections of original source material for research into the 1832 epidemic. Official government correspondence appears side by side with unofficial correspondence from private subjects from all strata of society. They provide an insight into Irish political, social, and economic history, letting us hear more than just an official voice.

Initial research in the 1831 and 1841 census abstracts, detail over 120 ‘civic centres’ – small towns with a population of over 2,000 inhabitants. A series of case studies is proposed and criteria will be used to collate data, which will allow examination of the progress and course of the disease on the ground, and in the different tiers of towns. All data will be input into a spreadsheet format, and further refined with appropriate statistical analysis. Kilkenny, Drogheda and Sligo were the most afflicted towns in Ireland, with a mortality rate equal to the worst urban areas in Europe. Here cases were so numerous, progress so rapid, and so singularly fatal at the first outbreak, that these places attached much attention at the time. Sligo’s mortality rate was 47.5 percent, just behind Waterford. But in terms of actual numbers of dead, Sligo had the highest number of deaths - 700 dead in six weeks - in all of the provincial towns, even ones with larger populations.

Ireland’s experience of the cholera epidemic ultimately provoked the involvement of the government into legislating more robustly, if somewhat reluctantly, for effective sanitation and public health. It helped to formulate the creation of a public health system with the coming of the Poor Law Act in 1838, and significantly influenced subsequent public health legislation in the half century after 1832.

[1] Timothy P. O’Neill, ‘Fever and public health in pre-famine Ireland’ in Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, vol. 103 (1973) 1-34: Joseph Robins, The Miasma: epidemic and panic in nineteenth century Ireland (Dublin, 1995), p.65: Cholera Board observations, (CSORP papers, National Archives of Ireland).

[2] Timothy P. O’Neill, ‘Fever and public health in pre-famine Ireland’ in Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, vol. 103 (1973) pp 1-34.